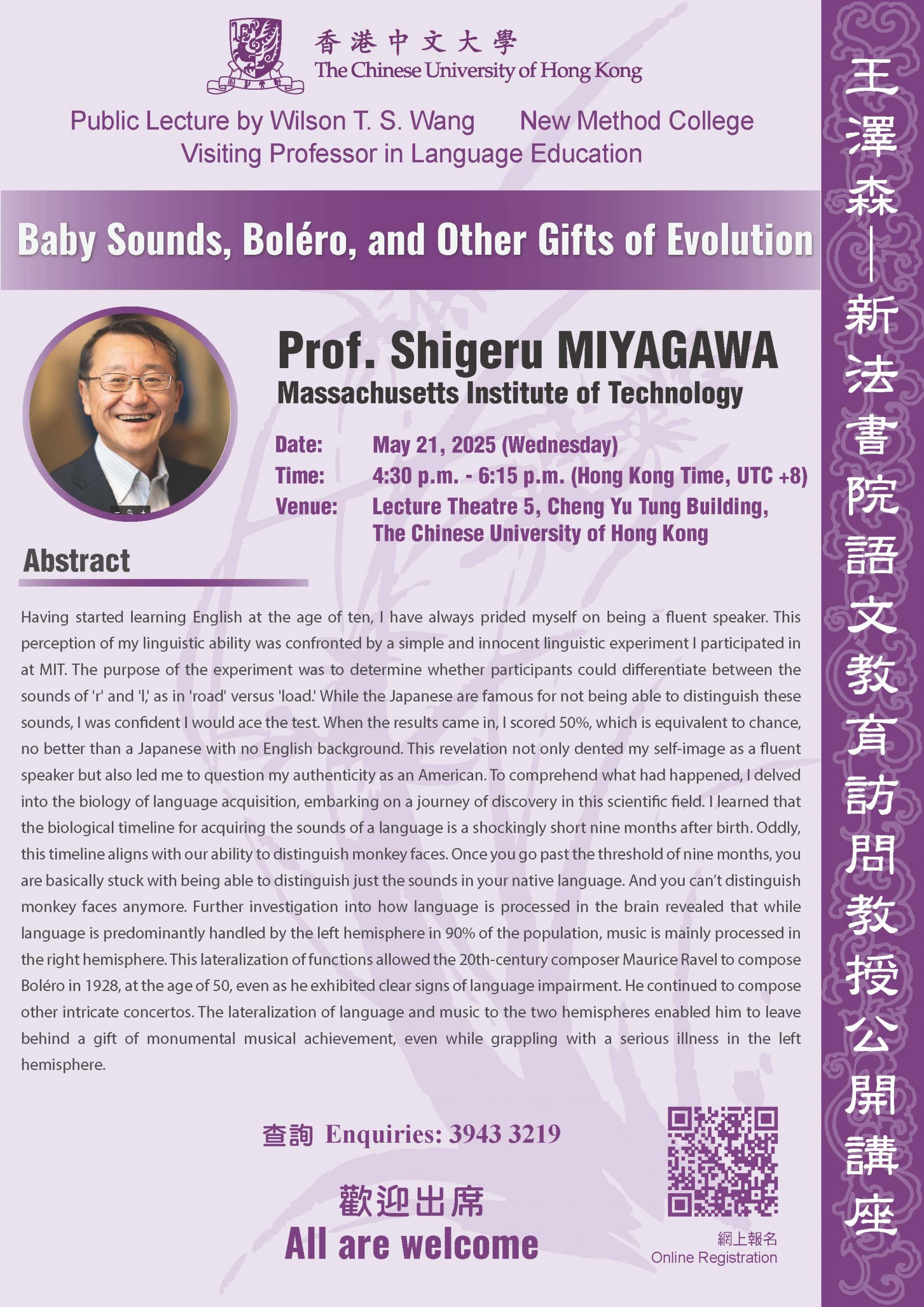

Speaker

Prof. Shigeru MIYAGAWA (MIT)

Professor Shigeru Miyagawa has been at MIT since 1991 as Professor of Linguistics and has held the Kochi-Manjiro Chair for Japanese Language and Culture. For the past twenty years, he has also been engaged with online education, and was the Senior Associate Dean of Open Learning until recently. From 2014 to 2019, he held a Project Professorship at the University of Tokyo as a cross-appointment with MIT. In September 2022, he was awarded the São Paulo Excellence Chair by the São Paulo Research Foundation for his work in language and evolution, and has been carrying out research as Visiting Professor of Biosciences at the University of São Paulo along with MIT.

He has published widely in linguistics, including three monographs in the Linguistic Inquiry Monograph Series from MIT Press, the most well-known monograph series in theoretical linguistics. He serves as an Editorial Board member for many major journals in the linguistic field, including Linguistic Inquiry, Journal of East Asian Linguistics, Glossa, and Journal of Japanese Linguistics. He has recently also started research on human evolution and language. A new paper by him just appears in Frontiers in Psychology, shedding light on the emergence time of human linguistic capacity through genomic evidence. His work is featured in a BBC Radio4 program, What the songbird said.

Title:

Baby Sounds, Boléro, and Other Gifts of Evolution

Abstract:

Having started learning English at the age of ten, I have always prided myself on being a fluent speaker. This perception of my linguistic ability was confronted by a simple and innocent linguistic experiment I participated in at MIT. The purpose of the experiment was to determine whether participants could differentiate between the sounds of ‘r’ and ‘l,’ as in ‘road’ versus ‘load.’ While the Japanese are famous for not being able to distinguish these sounds, I was confident I would ace the test. When the results came in, I scored 50%, which is equivalent to chance, no better than a Japanese with no English background. This revelation not only dented my self-image as a fluent speaker but also led me to question my authenticity as an American. To comprehend what had happened, I delved into the biology of language acquisition, embarking on a journey of discovery in this scientific field. I learned that the biological timeline for acquiring the sounds of a language is a shockingly short nine months after birth. Oddly, this timeline aligns with our ability to distinguish monkey faces. Once you go past the threshold of nine months, you are basically stuck with being able to distinguish just the sounds in your native language. And you can’t distinguish monkey faces anymore. Further investigation into how language is processed in the brain revealed that while language is predominantly handled by the left hemisphere in 90% of the population, music is mainly processed in the right hemisphere. This lateralization of functions allowed the 20th-century composer Maurice Ravel to compose Boléro in 1928, at the age of 50, even as he exhibited clear signs of language impairment. He continued to compose other intricate concertos. The lateralization of language and music to the two hemispheres enabled him to leave behind a gift of monumental musical achievement, even while grappling with a serious illness in the left hemisphere.

Enquires

For inquiry, please contact the General Office at +852 3943 3219.