Speaker

Prof. Niels GAUL

School of History, Classics and Archaeology

University of Edinburgh

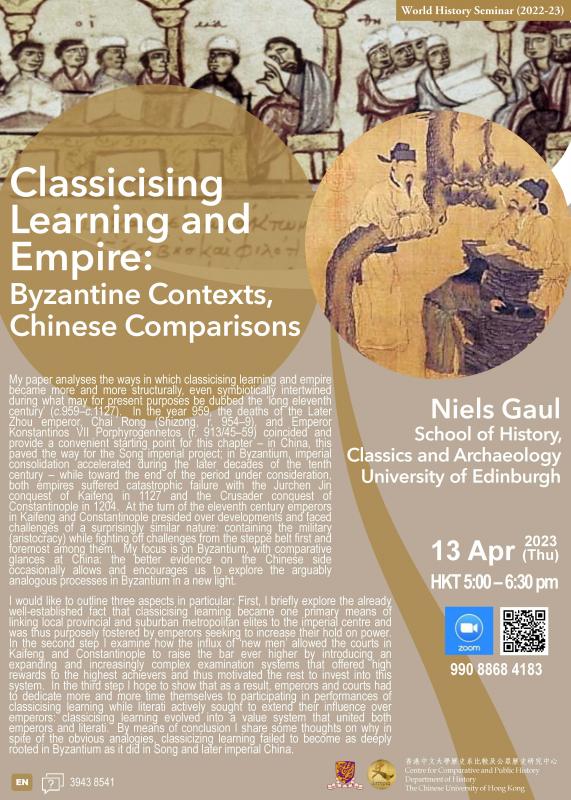

My paper analyses the ways in which classicising learning and empire became more and more structurally, even symbiotically intertwined during what may for present purposes be dubbed the ‘long eleventh century’ (c.959–c.1127). In the year 959, the deaths of the Later Zhou emperor, Chai Rong (Shizong, r. 954–9), and Emperor Konstantinos VII Porphyrogennetos (r. 913/45–59) coincided and provide a convenient starting point for this chapter – in China, this paved the way for the Song imperial project; in Byzantium, imperial consolidation accelerated during the later decades of the tenth century – while toward the end of the period under consideration, both empires suffered catastrophic failure with the Jurchen Jin conquest of Kaifeng in 1127 and the Crusader conquest of Constantinople in 1204. At the turn of the eleventh century emperors in Kaifeng and Constantinople presided over developments and faced challenges of a surprisingly similar nature: containing the military (aristocracy) while fighting off challenges from the steppe belt first and foremost among them. My focus is on Byzantium, with comparative glances at China: the better evidence on the Chinese side occasionally allows and encourages us to explore the arguably analogous processes in Byzantium in a new light.

I would like to outline three aspects in particular: First, I briefly explore the already well-established fact that classicising learning became one primary means of linking local provincial and suburban metropolitan elites to the imperial centre and was thus purposely fostered by emperors seeking to increase their hold on power. In the second step I examine how the influx of ‘new men’ allowed the courts in Kaifeng and Constantinople to raise the bar ever higher by introducing an expanding and increasingly complex examination systems that offered high rewards to the highest achievers and thus motivated the rest to invest into this system. In the third step I hope to show that as a result, emperors and courts had to dedicate more and more time themselves to participating in performances of classicising learning while literati actively sought to extend their influence over emperors: classicising learning evolved into a value system that united both emperors and literati. By means of conclusion I share some thoughts on why in spite of the obvious analogies, classicizing learning failed to become as deeply rooted in Byzantium as it did in Song and later imperial China.

ZOOM Meeting ID: 990 8868 4183

Meeting link: https://cuhk.zoom.us/j/99088684183