CUHK ARTS strives to be one of the best higher education institutions in Asia committed to research in the arts and humanities with global impact. Our academic staff is well-positioned to undertake cutting-edge interdisciplinary scholarship and collaborations.

Global

Innovative

Inspirational

Dean's Message

“We are pleased that in 2025, The U.S. News and World Report ranked CUHK as the 13th Best Global University for Arts and Humanities in the world, the very top Asian university in this category. This result continues a steady upward trajectory in recent years in the ranking agency’s assessment of humanities education and research at CUHK.”

[Call for Entries!] CUHK Poetry Contest 2025!

All CUHK students enrolled in the 2025 – 26 academic year are welcome to join this exciting event. Submit your poem online by 3 October, Friday (12noon, Hong Kong Time). For enquiries, please contact airp@cuhk.edu.hk.

01

02

Guidance

I am a

Student

Scholar

Member of the Public

- Why do I need to study at CUHK ARTS?

- Which programmes are suitable for me?

- What scholarships and awards can I apply for?

- Will I get academic advice?

Research & Scholarship

We are committed to bridging Chinese and Western traditions with innovative research.

As humanities scholars, we seek not only to contribute new knowledge and ideas, but also to become insightful and engaging educators.

Explore Research and Scholarship

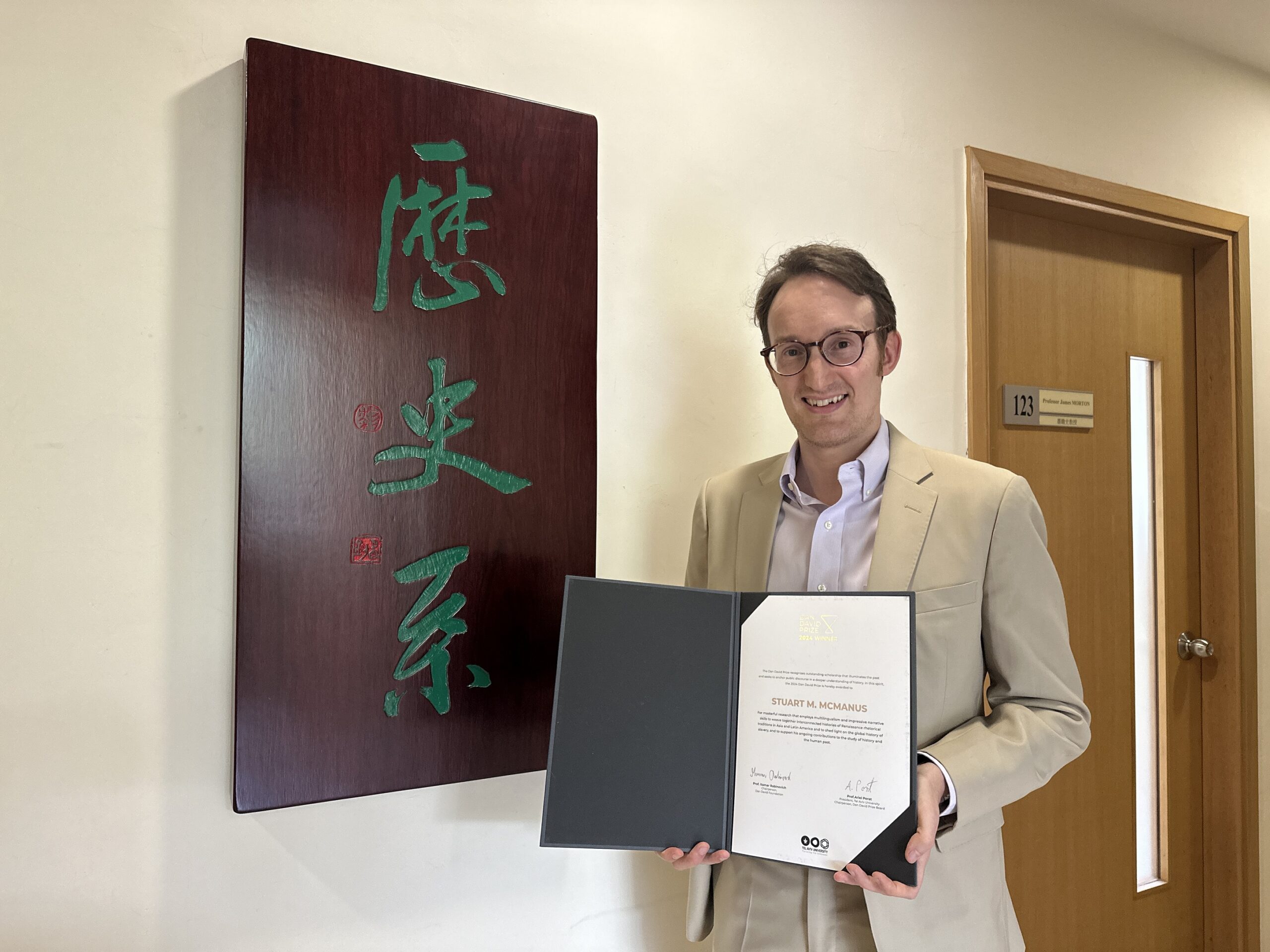

One Step Closer

Explore More Stories

Stories

CUHK and Yonsei Cultivate a Rich Tapestry of Cultural Learning

Stories

CUHK and Yonsei Cultivate a Rich Tapestry of Cultural Learning

Stories

The way to bring deaf and hearing people closer together – Film screening celebrates inclusiveness at CUHK

Stories

The way to bring deaf and hearing people closer together – Film screening celebrates inclusiveness at CUHK

The cast and crew of The Way We Talk, including director Adam Wong and actress Chung Suet-ying, and CUHK Professor Gladys Tang who supported the team with her work on deaf education, share their thoughts at the post-screening discussion

Professor Gladys Tang

Linguistics and Modern Languages

Explore More

Stories

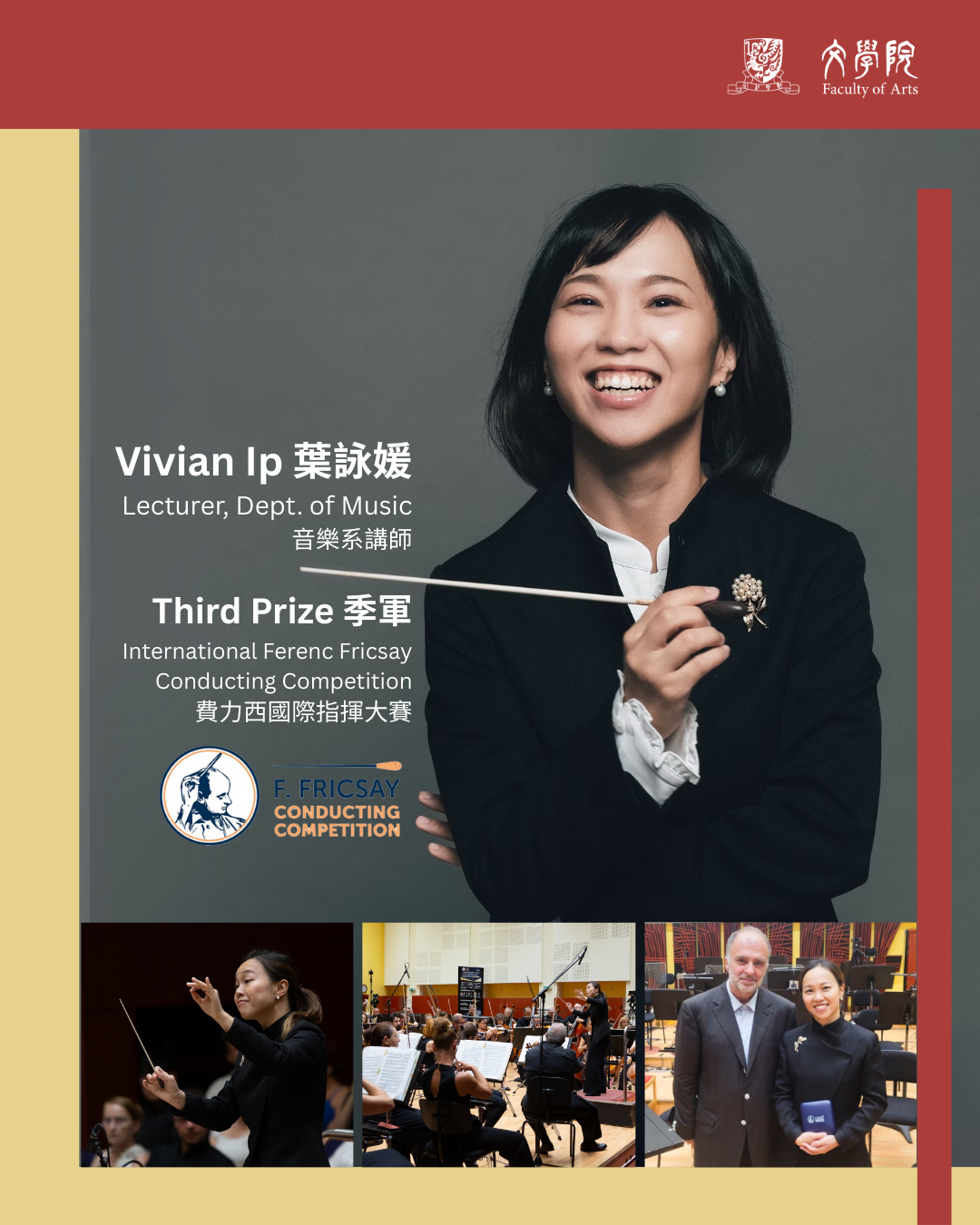

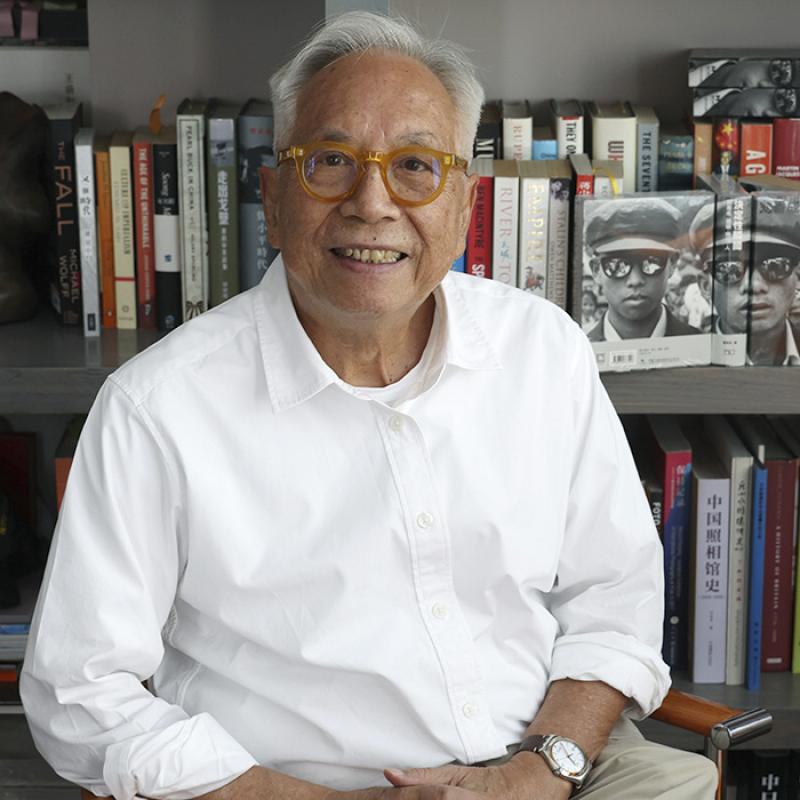

Art of documentary photography – Prize-winning photojournalist Liu Heung Shing has a date with CUHK in October

Stories

Art of documentary photography – Prize-winning photojournalist Liu Heung Shing has a date with CUHK in October

Over the last half a century, Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist Liu Heung Shing has been globetrotting with a camera and press pass to chronicle through his lens the first rough drafts of history.

Liu Heung Shing

/

Explore More

Stories

A True Renaissance Man

01

04

Latest Update

Explore More

There’s something

more to inspire you.

more to inspire you.

Discover what's current at CUHK ARTS.

![[Call for Entries!] CUHK Poetry Contest 2025!](https://www.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/web/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/CUHK-Poetry-Contest-2025_Poster2-scaled-1.jpg)